Professor Heiwai Tang and Mr Cyrus Cheung

18 December 2024

Through the ebb and flow of its economy in the aftermath of the Second World War, Hong Kong has sealed its status as an international financial and trade centre on the world’s economic stage. However, in light of the global economic downturn, fierce regional competition, and worsening geopolitical situation in recent years, coupled with the fact that Hong Kong–as a highly externally-oriented free economy–cannot afford to be complacent simply because it has historically managed to turn crises into opportunities. Times have changed. Now beleaguered by internal problems such as an ageing population as well as external challenges, the city may no longer be as “hardy” as it once was.

To address the challenges in the new era, Hongkongers should not stick to the old rut and must find ways to enhance competitiveness so that long-standing and thorny problems can be resolved.

Formidable problems facing the economy

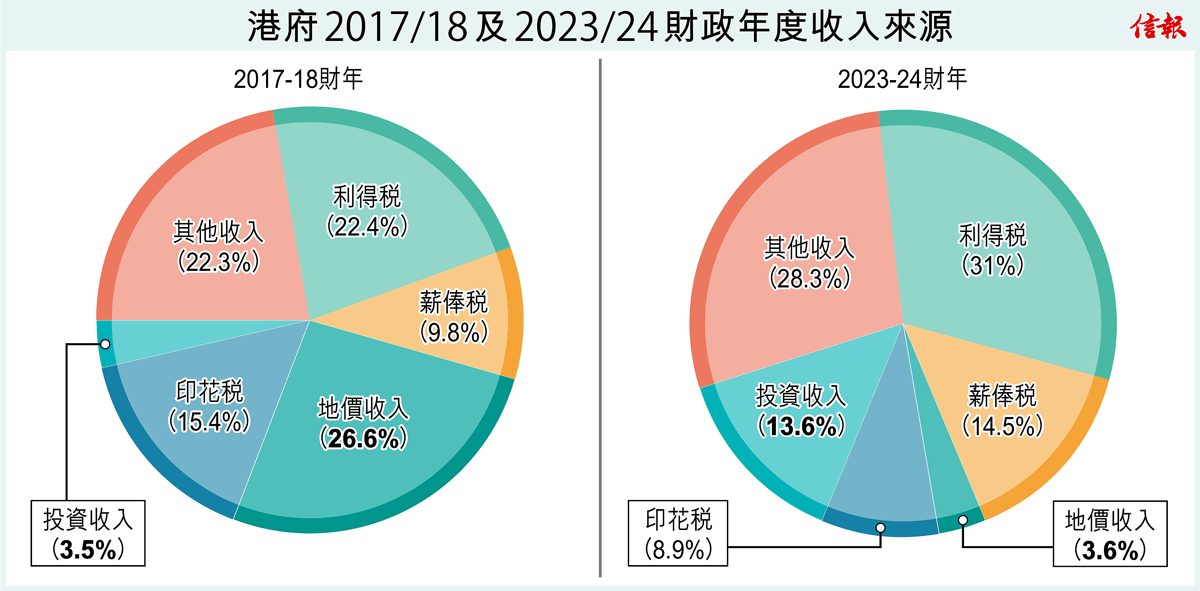

The first challenge facing the Hong Kong economy over the past few years is the SAR Government’s persistent fiscal deficits. After racking up a record-high surplus of $149 billion for 2017–18, the Government registered a fiscal deficit of $100.2 billion for 2023–24. Initially projected to be downsized to $48.1 billion for the current year 2024–25, the deficit is now estimated to reach $100 billion. Barring the reduction in income from Government-issued bonds, the actual deficit would be even larger. Factors underlying the deficits include fast-increasing government expenditures as well as decline in government revenues. Government expenditure soared significantly from $470.9 billion for 2017–18 to $721.3 billion for 2023–24, of which non-recurrent, social welfare, and healthcare expenditures grew the fastest. The last two items are unlikely to be cut. Meanwhile, government revenue dropped from $619.8 billion to $549.4 billion.

The Figure shows that in 2017–18, 26.6% of the Government’s main sources of revenue came from land premium while 15.4% came from stamp duties. In 2023–24, the share of land premium plummeted to 3.6% and stamp duties dramatically slumped to 8.9%. Despite seeing its share rise from 3.5% to 13.6%, investment income is, after all, not a stable source of revenue. In addition, the Inland Revenue Department annual report 2023–24 reveals that in the year of assessment 2022–23, only around 1.83 million people were required to pay salaries tax, which means that the tax base is still narrow. Given the overall economic downturn, it is unlikely that the Government will be able to sharply reduce the persistently-high fiscal deficits in the short run.

Figure Sources of the Hong Kong SAR Government revenue for 2017–18 and 2023–24

The second challenge facing the Hong Kong economy is the failure to fully leverage the economic benefits from the integrated development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area (GBA). Despite the high degree of integration of consumption activities in the GBA, Hong Kong’s professional services sector has yet to be fully integrated into the development of the GBA. While it has become a trend among Hongkongers to go north for spending, there is much less incentive for Mainlanders to spend in Hong Kong. At the same time, more and more local people prefer to shop on Mainland e-commerce platforms, inevitably impacting the sales of physical stores in Hong Kong. According to the Census and Statistics Department’s data, the Value Index of Retail Sales dropped from 144.8 points in 2018 to merely 121.3 points in 2023 while the monthly average for the first 10 months of 2024 went further down to 111.8 points.

Furthermore, the Volume Index of Retails Sales dropped from 148.9 points in 2018 to 113.9 points in 2023, and even averaged 103.3 points in the first 10 months of 2024. The decreases for both indexes are equally significant. Due to constraints in rent and labour costs, the local retail industry can hardly compete with its Mainland counterpart in terms of cost-effectiveness. It seems that the professional services industry, in which Hong Kong excels, has not been able to capitalize on the market opportunities in the GBA. This can be put down not only to the sluggish macroeconomy in recent years but also to delayed cross-boundary professional qualification certification, administrative red tape, and other factors.

The third challenge facing the Hong Kong economy is the gradual shrinking of the middle class and international talent drain. Hong Kong’s unitary economic structure is one of the primary reasons for the weakening middle class. Since middle-income jobs have always been concentrated in the financial, real estate, and professional services industries, problems will start to surface as soon as these sectors face headwinds. In addition, while there has been a mass migration of middle-class families overseas in the last few years, the highly-educated new immigrants to Hong Kong are less internationalized. The LinkedIn profile data analysed in an essay in the “Hong Kong Economic Policy Green Paper 2024” published by the HKU Business School demonstrates that the proportion of Asians among leavers is 58% and is as high as 79% among joiners, while the number of connections of leavers is 1.7 times that of joiners.

Four reform strategies to chart a new course

Cracking the above problems is no easy task. Let me outline below four policy directions to spark more valuable ideas from all sectors.

- Broadening the tax base to tap new revenue sources

Hong Kong can take a leaf from Singapore’s book and consider introducing consumption tax progressively to relieve financial pressure on the Government. The goods and services tax (GST) implemented in Singapore at a rate of 3% in 1994 gradually rose to 9% in 2024. In 2023, the GST contributed to 15.7% of Singapore’s fiscal revenue. Based on private consumption expenditure in Hong Kong, and after deducting existing overlapping tax items, a 2% GST can bring the Hong Kong SAR Government an incremental income of $27 billion, roughly equivalent to 5% of the financial revenue in 2023. Referencing Singapore’s experience, retail sales fell following upward adjustments of GST in 2007 and 2023, but not after GST hikes in 1994, 2003, and 2004. An economist at RHB Bank points out in a recent study that the GST increase in January 2024 did not have a strong impact on Singaporeans’ spending habits. This suggests that a GST rise does not necessarily dampen retail sales. The key lies in a balanced measure that entails controlled tax increases, effective expectations management, and complementary welfare policies to maintain steady consumer sentiment.

As a matter of fact, the introduction of GST in Singapore did arouse controversy. For example, there were views that daily necessities should be exempted. The Singaporean government did not accept this suggestion because of the potential increase in compliance and audit costs. Instead, the authorities chose to alleviate pressure on low-income families by issuing GST vouchers, subsidizing public education and healthcare services, etc. In any case, if the GST rate is set too low, it will not be adequate to alleviate the Government’s financial problems. Conversely, if the rate is set too high, it will breed dissatisfaction among businesses and the general public and could build up excessive inflationary pressure. How to strike a balance in between is a great challenge for policy formulation. Moreover, the Government can consider selling idle assets, including unused premises and surplus equity, to ease financial pressure.

- Fostering development via public-private partnerships

The SAR Government can consider strengthening public-private partnerships to promote infrastructure development. Apart from reducing the Government’s initial investment and operating costs, this approach helps to bring in technologies and management experience from leading enterprises. Many international cities have achieved remarkable results through this development mode. Examples include the Chicago Skyway and the Port of Long Beach Middle Harbour Redevelopment Project in the US, the Marina Bay Sands Integrated Resort in Singapore, the Beijing subway Line-4 project, and the Eastern Harbour Crossing in Hong Kong. There are, of course, different forms of public-private partnerships, with “Build, Operate, and Transfer”; “Build, Own, and Operate”; “Transfer, Operate, and Transfer” among the most common modes. Hong Kong can choose the suitable mode depending on its specific needs.

- Leveraging unique advantages to integrate into the GBA

Hong Kong needs to optimize its integration with other cities in the GBA to give full play to the benefits of the regional economy. According to the Second Agreement Concerning Amendment to CEPA Agreement on Trade in Services recently signed by the SAR Government with Mainland authorities, the Mainland market will be further opened up to Hong Kong enterprises offering professional services. On this basis, the SAR Government can continue to maintain close liaison and cooperation with other GBA cities to ensure the successful implementation of policies. For instance, assistance can be provided for Hong Kong’s estate surveying companies to complete the filing of records to bid for consultancy services projects in joint ventures within the GBA.

Given the distinct advantage of Hong Kong’s higher education in the GBA, the SAR Government can maintain close cooperation with sister cities and continue to support higher-education institutions in building branch campuses in the GBA and achieving success in their subsequent development. Opening up the “four flows”―human flow, goods flow, capital flow, and information flow―is of vital importance in this regard. Only by doing so will it be possible for the branch campuses in the GBA to obtain invaluable resources from both the Mainland and abroad, and for Hong Kong’s higher education institutions to preserve their competitive edge in internationalization.

To maximize the removal of operating restrictions on Hong Kong’s professional service sectors, such as finance, law, and accounting, in the GBA, the SAR Government needs to continue to lift systemic barriers in the area. For example, in the First Phase Report on Survey of the Current Situation of Hong Kong Legal Practitioners under the Development of the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, the Law Society of Hong Kong and the School of Law of Sun Yat-sen University point out that under Mainland laws, the associations formed by Hong Kong law firms with Mainland law firms shall not be in the form of partnership or legal entity. Therefore, cooperation between Hong Kong and Mainland law firms is mainly based on non-partnership associations. This gives rise to various problems, including differences in handling conflicts of interest, discrepancies in business acceptance and processing standards, and a lack of clarity on the legal responsibilities of non-partnership associations.

- Proactively competing for talent and enticing foreign investments

Apart from talent and capital from the Mainland, Hong Kong must also focus on attracting talent and funds from abroad to maintain its relative advantages as an international metropolis. In view of the fact that the career development of ethnic Chinese technology experts in Europe and the US is thwarted by current geopolitical tensions, the SAR Government should seize this opportunity to encourage them to advance their careers in Hong Kong. Meanwhile, the authorities can also consider setting specific performance indicators for local universities, e.g. target percentages for international students, to reinforce local higher education institutions’ strengths in internationalization.

Needless to say, Hong Kong must continue to leverage the unique advantage of “one country, two systems” to draw in more direct foreign investments to the Mainland. At the same time, apart from enticing Mainland investments through the Government’s Office for Attracting Strategic Enterprises, it is also necessary to enhance the presence of leading foreign enterprises to maintain Hong Kong’s distinctive advantage as a bridge to the world. The growth of emerging sectors, e.g. artificial intelligence, biotechnology, financial technology, advanced manufacturing, and new energy sources, will determine if Hong Kong can produce more high-quality jobs in future, thereby expanding its middle class and furthering its economic prosperity.

As we mentioned in this column two years ago, priority should be given to creating a liveable environment when it comes to attracting talent. Otherwise, they will not stay after arriving. On the one hand, they need to find high-quality jobs in Hong Kong, connect with a thriving professional community, and enjoy a comfortable and vibrant living environment. On the other hand, high-quality human capital is a key consideration for companies with an eye to establishing their presence in Hong Kong. Hence, efforts to attract companies and capital, compete for talent, or even formulate cultural policies should be complementary rather than isolated from one another. Retaining talent and businesses is a systemic project that requires comprehensive policy coordination across the SAR Government to achieve success.